When a woman was left with illegitimate children after her partner had died, she was examined by the local overseers of the poor to find out which parish she belonged to. Such an examination happened to Ann Howell …

On 27th April 1832, Mitcheldean Overseers of the Poor examined Ann Howell, the daughter of Evan and Mary Howell of Lampeter in Pembrokeshire as to where she had been born. She was 47 years old and in need of help from the parish. Her examination revealed a long story involving much travelling.

In 1813, Ann had been hired by Captain James Probert of St. David’s at £5, presumably in a domestic capacity. After she left Captain Probert’s employ she ‘connected’ with George Sleeman Kendal, a malt mill grinder. She never married him but lived and travelled with him. In 1814, she became pregnant and was delivered of a male bastard child at a lodging house in Pembroke. The child was baptised Thomas Sleeman Kendal in Peterchurch, Herefordshire. In 1820, Ann had a female bastard child at Brockway in Hewelsfield who was baptised Mary. In August of that year, a male bastard child called George was baptised at St Mary’s church in Swansea.

Then the family moved to Ruardean and finally Mitcheldean. In May 1822, a son called William was baptised, the following July a daughter called Margaret arrived on the scene and, finally, a sixth child, a boy called Evan after his grandfather, was baptised at Mitcheldean in August 1825.

The following year, George Sleeman Kendal died and Ann stated that she did not know his legal place of settlement but only that it was near Penzance in Cornwall.

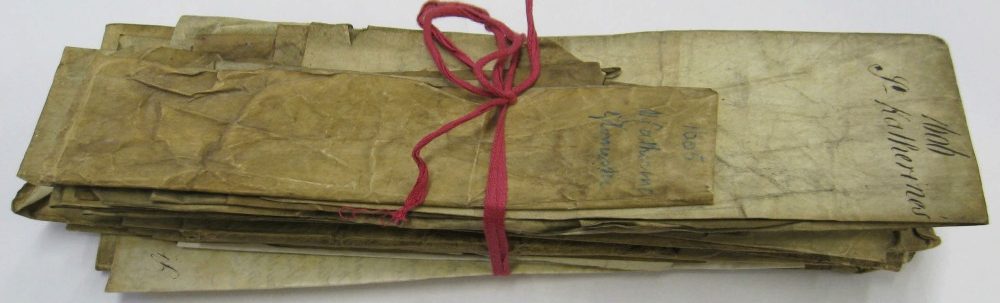

If it weren’t for this examination document, how confident would you be in tying the various baptisms together into one family?